Irena Sendler: A Hero of the Children and Their Mothers

“I was taught by my father that when someone is drowning, you don’t ask if they can swim. You just jump in and help.” Irena Sendler was never anyone to brag—she always said that she simply did what she had to do. What she did, however, was nothing short of extraordinary. A young Catholic Polish social worker from Warsaw, she saved the lives of at least 2,000 Jewish children, smuggling them out of the Warsaw Ghetto, an unbearably overcrowded, unsanitary, and dangerous section of the city the Nazis sealed off during their World War II occupation. The reader also learns of events in Irena’s earlier life that led her to do what she did, as well as what she did after the war, a person unknown to most of the world.

This excellent translation is our best source on the life of Irena Sendler. The research is thorough and come alive through the many interviews the author conducted with Irena herself and the people who knew her. Most notable is that Ms. Mieszkowska lets Irena tell her own story in her own words. It provided much of the source material for the beautiful PBS documentary, Irena Sendler: In the Name of Their Mothers.

Of particular interest to young readers are Irena’s activities in secret, underground organizations, including Zegota. Code names, forged documents, smuggling, and underground escape routes highlight the dangers Irena and her colleagues. Most remarkable was the rescue of a six-month-old infant in a wooden carpenter’s box. That baby, Elzbieta Ficowska, would grow up to become one of Irena’s closest and most trusted friends. Her story is told here.

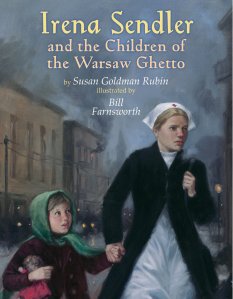

Persuading Jewish mothers to give up their young children was the most heart-rending part of Irena’s job. How she kept careful notes of each child and stored them in a jar is one of the highlights of Ms. Rubin’s book. And the author pays the ultimate homage to Irena by allowing her to state that she did not consider herself a hero—she did what she had to do. The real heroes, said Irena, were the mothers who gave up their babies, the Polish families who took them in, and the children themselves.

It was the request of Irena herself that her biography begin with the story of four high school girls from Uniontown, Kansas—half a world away and half a century from the terrifying experiences that defined her early life. That was Irena Sendler, a selfless person doing what she considered her moral duty.